REX/Shutterstock

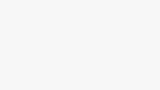

REX/ShutterstockExactly two months after her election loss to Donald Trump, Vice President Kamala Harris will preside over the certification of her own defeat.

As president of the Senate, she will stand at the House Speaker’s rostrum on Monday to preside over the counting of Electoral College votes, officially cementing her rival’s triumph two weeks before he returns to the White House.

The circumstances are painful and awkward for a candidate who dismissed her opponent as a pressing threat to American democracy, but Harris aides insist she will carry out her constitutional and legal duty with seriousness and grace.

It’s not the first time a losing candidate will lead a joint session of Congress to count their opponent’s presidential nominees — Al Gore endured the indignity in 2001 and Richard Nixon in 1961.

But it’s a fitting coda to an unlikely election that saw Harris elevated from a back-up to the nation’s oldest president to the Democratic standard-bearer — whose volatile campaign gave her party a jolt of hope before a crushing loss exposed deep internal fault lines.

Harris and her team are now considering her second act, weighing whether that includes another run for the White House in 2028 or pursuing a bid for the governor’s mansion in her home state of California.

While recent losing Democratic candidates — Al Gore, John Kerry, Hillary Clinton — have decided not to seek the presidency again, aides, allies and donors say the overwhelming support Harris garnered in her failed bid and the unusual circumstances of her condensed campaign. proving there’s still a chance she could seek the Oval Office.

They even point to Donald Trump’s own rewritten political path — the former and future president’s bookend wins in 2016 and 2024, despite losing as the incumbent in 2020.

But while many Democrats don’t blame Harris for Trump’s victory, some — stung by a landslide loss that has called into question the party’s strategy — are deeply skeptical of giving her another shot at the White House. A host of Democratic governors who rallied behind the vice president in 2024 but have ambitions of their own are seen by some strategists as fresher candidates with a much better chance of winning.

Reuters

ReutersHarris herself is said to be in no rush to make any decisions, telling advisers and supporters that she is open to all the possibilities that await her after Inauguration Day on January 20.

She assesses the past few months, during which she launched a brand new White House campaign, vetted a candidate, chaired a party convention and stormed the country in just 107 days. And aides point out that she will remain the US vice president, at least for another two weeks.

“She has a decision to make and you can’t make it when you’re still on the treadmill. It may have slowed down — but she’s on the treadmill until January 20,” said Donna Brazile, a close Harris ally. who advised campaign.

“You can’t put anybody in a box. We didn’t put Al Gore in a box, and it was clear that the country was very divided after the 2000 election,” said Brazile, who ran Gore’s campaign against George W Bush, pointing to his second life as an environmental activist. “All options are on the table because there is an appetite for change and I believe she can represent that change in the future.”

But the nagging question overshadowing any potential 2028 run is whether the 60-year-old can separate herself from Joe Biden — something she failed to do on the campaign trail.

Her allies in the party say Biden’s choice to seek re-election despite concerns about his age, only then to ultimately drop out of the race with months remaining, doomed her candidacy.

Although Trump swept all seven battleground states and is the first Republican in 20 years to win the popular vote, his margin of victory was relatively narrow, while Harris still won 75 million votes, a result her supporters argue cannot be ignored as a moment faceless Democratic Party rebuilding over the next four years.

On the other hand, those close to Biden remain convinced that he could have defeated Trump again, despite polls showing that he had softened the support of key Democratic voting blocs.

They point out that Harris fell short where the president did not in 2020, underperforming with core Democratic groups like black and Latino voters. Critics continue to pick on her 2019 campaign to become the Democratic presidential nominee, which fizzled out in less than a year.

“People forget there had been a real primary [in 2024]she would never have been the nominee. Everybody knows that,” said a former Biden adviser.

The adviser, who spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss a sensitive matter, applauded Harris for reviving the Democratic base and helping key congressional races, but said Trump’s campaign successfully undercut her on critical campaign issues, including the economy and the border.

Reuters

ReutersHowever, members of Trump’s team, including his chief pollster, have acknowledged that Harris fared more strongly as a candidate than Biden on certain issues such as the economy among voters.

Still, there’s no avoiding that any Democratic primary contest for 2028 would be a tight battle, with rising stars like Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, Illinois Gov. JB Pritzker and California Gov. Gavin Newsom already weighing in on the presidential candidates.

Some Democrats say Harris would nonetheless start ahead of the pack with national name recognition, a highly coveted mailing list and a deep bench of volunteers.

“What state party wouldn’t want her to come and help them set the table for the 2026 midterm elections?” Brazile said. “She will have plenty of opportunities not only to rebuild but to strengthen the coalition that came together to support her in 2024.”

Others have suggested she could step out of the political arena altogether, run a foundation or establish a political institute at her alma mater, Howard University, the Washington-based historically black college where she held her election-night party.

The former top state attorney could also be a candidate for secretary of state or attorney general in a future Democratic administration. And she will have to decide if she wants to write another book.

For all her opportunities, Harris has told aides, she wants to remain visible and be seen as a leader in the party. An adviser suggested she could exist outside the domestic political fray and take on a more global role on an issue that matters to her, but that’s a difficult perch without a platform as big as the vice presidency.

Reuters

ReutersIn the waning days of the Biden-Harris administration, she plans to take an international trip to several regions, according to a source familiar with the plans, signaling her desire to maintain a role on the world stage and build a legacy beyond Biden’s . number two.

For Harris and her team, the weeks since the election have been humbling, a mix of grief and determination. Several aides described the three-month sprint that began when Biden dropped out as beginning with the campaign “digging out of a hole” and ending with their candidate more popular than when she began, even though she didn’t win.

“There’s a sense of peace in knowing that given the hand we were dealt, we ran through the tape,” said a senior aide.

After the election, Harris and her husband, Second Gentleman Doug Emhoff, spent a week in Hawaii with a small group of aides to relax and discuss her future.

During a staff party at her official residence before Christmas, Harris recounted election night and how she gave a pep talk to her family when the results came in.

“We’re not having a pity party!” she told the audience about her reaction that night.

Advisers and allies say she is still processing what happened and wants to wait and see how the new administration unfolds in January before laying out any position, let alone seeking to become the face of any so-called Trump “resistance”.

Democrats have found that the resistance movement that took off among liberals in the wake of his 2016 victory no longer resonates in today’s political climate, where the Republican has proven his message and style appeal to a broad cross-section of Americans.

They have adopted a more conciliatory approach to confronting the incoming president’s agenda. As several Democrats put it, “What opposition?”

Although she has kept a relatively low profile since her loss, Harris offered a glimpse of her thinking at an event for students at Prince George’s Community College in Maryland in December.

“The movements for civil rights, women’s rights, workers’ rights, the United States itself would never have come into being if people had given up their cause after a trial, a fight or an election didn’t go their way,” she said.

“We’re going to stay in the fight,” she added, a refrain she’s repeated since her Senate victory in 2016. “All of us.”

EPA-EFE/REX/Shutterstock

EPA-EFE/REX/ShutterstockWhat that means is less clear. For some donors and supporters, getting “in the fight” could translate into a run for California governor in 2026, when a term-limited Gavin Newsom will step down and potentially pursue his own White House ambitions. The job leading the world’s fifth-largest economy would also put Harris in direct conflict with Trump, who has regularly attacked the state for its left-leaning policies.

But governing a major state is no small feat, and it would derail any presidential run, as she would be sworn into office around the same time she was set to launch a national campaign.

Those who have spoken with Harris said she remains uncertain about the governor’s race, which some allies have described as a potential “capstone” to her career.

She has won statewide office three times as California Attorney General and later as a US Senator. But a gubernatorial victory would give her another historic honor — becoming the nation’s first black female governor.

Still, some allies acknowledge that going from being inside a 20-car motorcade and having a seat across the table from Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky to the governor’s mansion would be difficult.

The private sector is another option.

“For women at other levels of office, when they lose an election, opportunities are sometimes not as available to them compared to men who get a soft landing at a law firm or insurance company, and that gives them a place to take a beat, earn some money and then make decisions about what’s next,” said Debbie Walsh, director of the Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers University.

“I don’t think it’s going to be a problem for Kamala Harris. I think doors will open for her if she wants to open them.”

But for Harris, who has been elected for two decades and worked as a prosecutor before that, an afterlife as governor may be the most fitting option.

“When you’ve had one client — the people — your whole career,” said one former adviser, “where do you go from here?”