BBC

BBCKennesaw, Georgia has every small town imaginable in the American South.

There’s the smell of baked biscuits from Honeysuckle Biscuits & Bakery and the rumble of a nearby railroad train. It’s the kind of place where newlyweds leave handwritten thank-you cards in coffee shops and praise the “nice” atmosphere.

But there’s another aspect of Kennesaw that some might find surprising — a city ordinance from the 1980s that legally requires residents to own guns and ammunition.

“It’s not like you walk around wearing it on your hip like the Wild Wild West,” said Derek Easterling, the city’s three-term mayor and self-described “retired Navy guy.”

“We’re not going to knock on your door and say, ‘Let me see your weapon.'”

Kennesaw’s gun law states plainly: “In order to provide for and protect the safety, security and general welfare of the city and its inhabitants, every head of household residing within the city limits is required to maintain a firearm together with ammunition.”

Residents with mental or physical disabilities, felonies or conflicting religious beliefs are exempt from the law.

As far as Mayor Easterlings and several local officials are aware, there have been no prosecutions or arrests for violations of Article II, § 34-21, which took effect in 1982.

And no one the BBC spoke to could say what the penalty would be for being found in breach.

Still, the mayor insisted, “It’s not a token law. I’m not into things just for show.”

For some, the law is a source of pride, a nod to the city’s embrace of gun culture.

For others, it is a source of embarrassment, a page in a chapter of history they wish to move beyond.

But the main belief among townspeople about the gun law is that it keeps Kennesaw safe.

Patrons eating pepperoni slices at the local pizzeria will suggest, “If anything, criminals should be worried because if they break into your home and you’re there, they don’t know what you’ve got.”

There were no homicides in 2023, according to Kennesaw Police Department data, but there were two gun-involved suicides.

Blake Weatherby, a groundskeeper at Kennesaw First Baptist Church, has different thoughts on why violent crime may be low.

“It’s the attitude behind the guns here in Kennesaw that keeps gun crime down, not the guns,” said Mr. Weatherby.

“It doesn’t matter if it’s a gun or a fork or a fist or a high-heeled shoe. We protect ourselves and our neighbors.”

Pat Ferris, who became a Kennesaw City Council member in 1984, two years after the law was passed, said the law was created to be “more of a political statement than anything else.”

After Morton Grove, Illinois became the first US city to ban gun ownership, Kennesaw became the first city to require it, sparking national headlines.

A 1982 op-ed by the New York Times described Kennesaw officials as “jovial” about the law’s passage, but noted that “Yankee criminologists” were not.

Penthouse Magazine ran the story on its cover with the words Gun Town USA: An American Town Where It’s Illegal Not to Own a Gun printed over a picture of a bikini-clad blonde woman.

Similar gun laws have been passed in at least five cities, including Gun Barrel City, Texas, and Virgin, Utah.

In the 40 years since Kennesaw’s gun law was passed, Mr. Ferris, its existence has mostly faded from consciousness.

“I don’t know how many people even know the ordinance exists,” he said.

In the same year that the Arms Act came into effect, Mr Weatherby, the church’s landowner, was born.

He recalled a childhood when his father half-jokingly told him, “I don’t care if you don’t like guns, it’s the law.”

“I was taught that if you’re a man, you have to own a gun,” he said.

Now 42, he was 12 years old the first time he fired a weapon.

“I almost dropped it because it scared me so bad,” he said.

Mr Weatherby owned over 20 guns at one time but now said he owns none. He sold them over the years – including the one his father left him when he died in 2005 – to get through hard times.

“I needed gas more than guns,” he said.

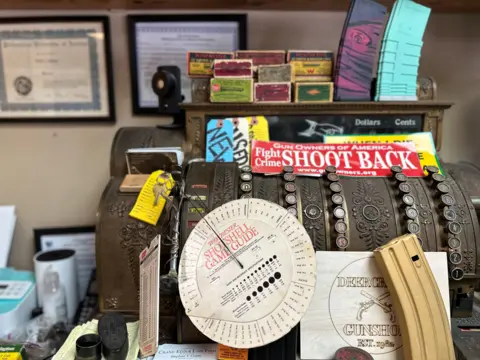

One place he could have gone to sell his firearms is the Deercreek Gun Shop located on Kennesaw’s Main Street.

James Rabun, 36, has worked at the gun shop ever since he graduated high school.

It is the family business, he said, opened by his father and grandfather, both of whom can still be found there today; his father in back restoring firearms, his grandfather in front relaxing in a rocking chair.

For obvious reasons, Mr. Rabun fan of Kennesaw’s gun laws. It’s good for business.

“The cool thing about firearms,” he said with serious enthusiasm, “is that people buy them for self-defense, but a lot of people like them, like art or bitcoin — things of scarcity.”

Among the dozens and dozens of guns hanging on the wall for sale are double-barreled black powder shotguns—akin to a musket—and a pair of “they-don’t-make-these-anymore” Winchester rifles from the 1800s.

In Kennesaw, gun fandom has a broad reach that extends beyond gun shop owners and middle-aged men.

Cris Welsh, mother of two teenage daughters, is unabashed about her gun ownership. She hunts, is a member of a gun club and shoots at the local gun range with her two girls.

“I’m a gun owner,” she admitted, listing her inventory, which includes “a Ruger carry pistol, a Beretta, a Glock and about half a dozen shotguns.”

However, Ms Welsh is not happy about Kennesaw’s gun laws.

“I’m embarrassed when I hear people talk about gun laws,” Ms Welsh said. “It’s just an old Kennesaw thing to hang on to.”

She wanted when outsiders thought of the city, they remembered the parks and schools and community values — not the gun laws “that make people uncomfortable.”

“There is so much more to Kennesaw,” she said.

City Councilor Madelyn Orochena agrees that the law is “something that people would rather not advertise.”

“It’s just a weird little factoid about our community,” she said.

“Residents will either roll their eyes in a bit of shame or laugh along.”